Group 17 – Teaching Science for Social Justice (11/16)

Teaching Science for Social Justice: Chapter 8 – Empowering Science Education and Youth’s Practices of Science

Summary:

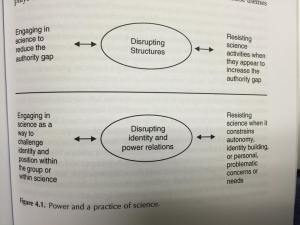

This chapter was mainly a summary of all the overarching ideas presented throughout the book, linking together different concepts that were presented in isolation into a bigger picture (Figure 8.1) and evaluating their roles. The chapter then explores possible future directions that we as educators can explore. In designing future curriculum, we need to keep in mind topics that allow students to see science: 1) “through multiple points of entry”, 2) “through structures that recognize networks” and 3) “through thinking about identities and relationships through a desire for change”. The book ends with a reminder, or author’s thoughts, on why we should pursue science education as a career.

Connection to class:

- This chapter came in a timely manner in tandem with our Case Study assignment where we were forced to think about our roles in classrooms in the future. Members of the group were able to apply our PLC readings to this assignment in our analysis of the case study assignment.

Highlights of Group Discussion:

- We talked a little bit about the Paris attacks and how Facebook let people “check in” that they were safe. We talked about how people had a problem with this, in that they are asking, “Why does FB only care about people in Paris, and not anywhere else in the world that are getting terrorized?

- We decided this was unfair, but it also made us feel like no matter what is done that is good, someone will always find a way to show you how wrong your good is.

- We also talked about how we are sad this is our second to last PLC! This semester has flown by. Three of the four of us are student teaching next semester, and although we are excited, we realized we only have 9 days of classes left of our undergraduate career which is CRAZY!

Questions to Pose (for the teacher’s panel next week):

- Has a student ever exhibited an insensitive response (e.g. laughing, ridiculing, mocking) to a social justice topic you were trying to teach your class? How did you respond to this situation?

- How much energy should/can we devote to incorporating social justice topics into our science curricula? How can we go about this in a tactful way?

- Has it been hard to balance making sure you are not offending someone in whatever you do? Like we were talking about from our first two discussion highlights, it seems that no matter what we do that is “good,” someone somewhere will find it offensive.

Mission Statement:

There was no change in our mission statement aside from the qualifications made from last week’s readings.

Next Week’s Reading:

Since we’ve completed the book, we’ll be revisiting the book in its entirety and discussing the overarching ideas, how they relate to what we’ve learned in the course this semester, and how we can apply them to our future careers.

Teaching Science for Social Justice: Chapter 7 – Building Communities in Support of Youths

Group 17 – Teaching Science for Social Justice (11/9)

Summary: In this chapter, we are introduced to the REAL (Restoring Environments and Landscapes) science community at Southside Shelter in New York City. In particular, the author explores the importance of collaboration in the scientific endeavors (and eventually accomplishments) of the science community in this urban setting. Individuals at the shelter not only draw from each other’s individual strengths, but also engage in dialogue (e.g. “courtyard chats”) to identify the needs and wants of the larger community. The author proposes that this inquiry-based approach to doing science has potential even in more traditional classroom settings.

Connection to class:

- Nieto (2009) talks about the importance of modifying instruction to be culturally sensitive which is reminiscent of the concept of “Inclusivity” discussed in this chapter. The need for “responsiveness and respect” also ties in with Nieto’s argument that cultural sensitivity should be emphasized in the classroom.

- Everyone comes to the classroom with different experiences and knowledge, based upon the circumstances they are born into (Hochschild, 2003), which was a concept the chapter revisited when contextualizing a Science classroom in a lower income area.

Highlights of Group Discussion:

- We talked about why one of our group members, René Kronlage, decided to join Teach For America. She knew she had to be a teacher after watching the movie Precious and was inspired by the teacher. From there she looked more into the program.

- A main argument against TFA is that it perpetuates the problem of there being a “revolving door of teachers,” and research has found that most lower-income, struggling schools have this revolving door of teachers. René brought up a good point, in that correlation does not equal causation, and asked us to think about the underlying issues that could be leading to this (i.e. lack of resources, not as much support from faculty, etc.). Why would a teacher want to continue teaching in a lower-income school if he or she isn’t supported and there is such a severe lack of resources, when they could transfer to another, better-funded school where their jobs would not be as stressful?

- Bryan Wang is currently deciding whether he wants to student teach next semester in an Honors Biology classroom, or in a classroom where his students are dropout students. From observing classrooms and his knowledge of both schools, the Honors Biology classroom would probably be much easier and less stressful, however he would have a lot of support teaching the high school dropouts Biology, so it would be much more rewarding. He also feels that if he could get through teaching next semester with these students, that he would learn a lot more about the “real world” in how hard teaching is and it would be much more rewarding. We will keep you updated on what he decides!

Questions to Pose:

- What does it mean to participate in a science community?

- How do decisions around who can participate and what participation entails influence the purposes, goals, and outcome of that community?

Who should be able to participate in a science community and how should participation be measured?

Mission Statement:

There was no change in our mission statement aside from the qualifications made from last week’s readings.

Next Week’s Reading:

Chapter 8 – Empowering Science Education and Youth’s Practices of Science: Under the same assumptions as last week in that later chapters refer back to stories in previous chapters and hence a chronological approach towards our readings were adopted. Through this reading, we will be reading more personal stories of individual students with a focus on geographical locations.

In-class Science vs. After-school Science

Our last post ended with the thought of how this after-school program translates into science that can be taught in the classroom. After reading chapter 5 of Teaching Science for Social Justice, we realized that the children decided that what they were doing, creating blueprints and eventually building a picnic table, did not coincide with their definition of “science.” The children thought that what they were doing focused more on simple construction compared to the traditional science experiments that teachers would lead in a classroom. We were curious in a similar manner, wondering if these projects that were supposed to be science-based actually encouraged these children in the shelter to learn more of science and to potentially pursue science in the future. Each subject has a set of standards that the teacher must follow, and so with this in mind, we wondered if this after school program supported at least some of the standards that would be met in the classroom.

These students would usually not enjoy science being taught in a traditional classroom, thus they turn to this after-school program to basically encourage their initiative to learn topics science-related. Yet, how could building a picnic table be considered science and fulfill standards that need to be met in the classroom? This was our concern when reading this chapter. Although the ideas in this book have great intentions, can these ideas be incorporated into the classroom? It would be ideal if science classes can utilize the ideas of their students to come up with student-centered activities that not only gauge the interests of the students, but also be beneficial to the community.

For this upcoming week, we will be discussing chapter 6 in hopes of our questions being answered.

Group 17 – Teaching Science for Social Justice (11/2)

Teaching Science for Social Justice: Chapter 6 – Transformations: Science as a Tool for Change

Summary: In this chapter, we are introduced to a young Black Cuban American man named Darkside who lives at an inner city New York homeless shelter. Darkside is in the 10th grade and has dreams of graduating and making a life for himself, but he encounters many obstacles along the way. Among them are the dangers of gang violence and, of course, the hardships of living at the homeless shelter, without a place to call his own. Nonetheless, we see Darkside making great strides towards his goals by engaging with a community science effort to beautify the surrounding area with a garden. Through his enthusiasm and leadership, he is also helping to transform his community.

Connection to class:

- Barry (2005) talks about how people who are advantaged (socioeconomically, by race, by association) have more opportunities to have access to a quality education and educational experiences. Similarly, he discusses how some students are disadvantaged by these very reasons and how they have to overcome much more challenges to get where the more advantaged students are. This creates a cycle were those who are at the top of the socioeconomic chain remain there, while those at the bottom remain there, too.

- Some factors that affect whether students end up ahead that Barry (2005) mentions include:

- Lack of parental care

- Lack of regulation in childcare

- Childcare

- Income level

- Encouragement

- Cultural resources

- Prenatal care

- Child abuse

- Maternity/Paternity leave

- Number of words child is exposed to a year

- Disability resources

- Access to technology

- Technology use ability

- Private Vs. Public schools

- Flexibility of time off

- Political viability

- Gerrymandering

- Some factors that affect whether students end up ahead that Barry (2005) mentions include:

- Bettez also argues that “Racism is a problem for us all.” In this sense, racism is negatively affecting Darkside.

Highlights of Group Discussion:

- Relating Darkside’s experience to personal experiences in schools as well as in-class observations as part of our pedagogical classes, although at a less extreme degree.

- Linking ideas shared in class presentations today to the PLC reading and discussing lesson ideas that could have been helpful in utilizing science as a tool for positive change in these classrooms.

- We talked about how science can empower students to want to go out and do things like make a community garden.

Questions to Pose:

- How can we guide students to use the knowledge they have to help them succeed in the classroom?

- How can we involve students in community projects like creating a community garden?

- How can science be used as a “tool for change” in that science can make students feel empowered to go above and beyond?

Mission Statement:

There was no change in our mission statement aside from the qualifications made from last week’s readings.

Next Week’s Reading:

Chapter 7 – Building Communities In Support of Youths’ Science Practices: Under the same assumptions as last week in that later chapters refer back to stories in previous chapters and hence a chronological approach towards our readings were adopted. Through this reading, we will be reading more personal stories of individual students with a focus on geographical locations.

Making the Most of Students’ Human and Social Capital

Teaching Science for Social Justice: Chapter 5 – Relevant Science: Activating Resources in Nonstandard Ways

Summary: Students at the Hope Shelter engaged with science by building their own picnic table. As part of this process, students developed their designs on paper, created small models, and then constructed their table from scratch. Different students were able to contribute and excel at different stages of the process. This chapter emphasizes the importance of understanding the intersection of human and material resources, as each student offers his or her own set of skills and experiences to projects that contribute to learning. Going off of this, it is also very important to understand the intersection between social and human capital so that students can feel a sense of ownership and pride over their work, so that each student feels they have contributed to the project by adding their own talents and skills to a specific aspect of the end goal.

Connection to class:

- Everyone comes to the classroom with different experiences and knowledge, based upon the circumstances they are born into, directly relating to the idea that inequalities are perpetuated by their family background (Hochschild, 2003).

- Cultural capital (Lareau, 1987), directly dictates the different types of “relevant science” one chooses to teach in school. The example of picnic tables may not be otherwise be relevant in a different context based upon the community and infrastructure of other schools.

Highlights of Group Discussion:

- When it comes to creative projects, children are more interested when they see that something they create is worthwhile.

- It is important to pull in students’ interests and variety of talents.

- When providing students with feedback, teachers should validate students’ feelings, goals, and aspirations while also exposing them to alternative options and opportunities.

- It is important to make students feel included in projects even if their friends live far away or do not attend the same school. Students, such as Ruben, can be reluctant to join in an activity if they feel that they have no friends to share it with.

Questions to Pose:

- When it comes to creative projects, what is the role of the teacher? At what point, if at all, should the teacher intervene and modify the student’s potentially flawed plans?

- How can we reinforce positive behavior in the classroom? Ruben was sent to behavior modification counseling for not writing his sentences. How can we, as teachers, help students want to do their work?

Mission Statement:

There was no change in our mission statement aside from the qualifications made from last week’s readings.

Next Week’s Reading:

Chapter 6 – Transformations: Science as a Tool for Change: Under the same assumptions as last week in that later chapters refer back to stories in previous chapters and hence a chronological approach towards our readings were adopted. Through this reading, we will be reading more personal stories of individual students with a focus on geographical locations.

The Power of Language in Science Curriculum

The NGSS (Next Generation Science Standards) is a program currently implemented in twenty six states across our nation. Next year, the state of North Carolina is going to be voting on the implementation of this science curriculum into our public school system. Because of this, our group thought it might be interesting to compare the current NC State Standards with the Next Generation Science Standards; specifically, the language used in the objectives and prompts. Right off the bat, it is easy to see very blatant differences in the wording of the two curriculums. The verbs used in the current NC curriculum outline lends itself to very passive instruction. Reading down a bulleted list of instructions you will see:

- explain …

- explain ….

- explain …

- summarize …

- explain …

- identify …

When you compare this to the the NGSS, you will see a much different pattern:

- analyze …

- develop a model …

- plan …

- conduct an inverstation …

- construct an argument …

These verbs provide aid to help a teacher learn to engage her students. There is no doubt in my mind that the students of a teacher following the Next Generation curriculum will be much more invested and intrigued by science and the learning process when compared to a student being taught by the current North Carolina guidelines.

Because the curriculum is just a list of objectives and topics for teachers to cover, teachers can relay this information to their students in any way they desire. It is easier for teachers to just pass out worksheets and lecture in order to reach the standards that they need to reach rather than going out side and doing a larger project and getting students engaged. The NGSS standards are what I would expect a teacher like the one in our book to be using. These teachers created a large class project engaging the community- which is much more interactive and inquiry based than a standard classroom would be. To promote innovation in our classrooms, it is time for our state to adjust their standards.

Questions of Power and Identity in Science Education 10/12

Teaching Science for Social Justice: Chapter 4 Power and Co-opting Science Spaces

Summary:

Junior & Iris

- Struggle between negotiating power in science and their lives: Junior and Iris both associate doing poorly in school with behavior/”being bad,” and they liked or disliked their teachers based on the respect they demonstrated toward her.

- If they felt disrespected, the were likely to challenge authority, thus “being bad.” Their thought process was that the “bad” kids did bad in school, whereas the “good” children did well in school.

- Junior wants to hammer things for a living, for this is what he sees many of the adults in his life doing for a living.

- Iris was extremely attached to her cultural identity as a Mexican and very loyal to her family–her siblings in particular. She took on much of the responsibility of a mother, and seemed very confused about her role as a sister (child) or mother (adult). Although Iris was smart, she was quick to give up if she didn’t do well at something right away–she was always “questioning the validity of her own choices.”

Co-Opting:

- If given the opportunity, students of varying backgrounds have been observed to “co-opt” their interactions with science, to gain ownership over their learning and make their interaction with science authentically their own. Thus the author purports that as much as possible, students should be presented with chances to co-opt their education.

Connection to class: In Chapter 4, Barton explains how student actions which are often perceived as “resistant” are in fact expressions of identity and means of self-preservation. This connects to the Barry (2005) reading, where we encountered that students’ deviant behavior, often deemed “not socially acceptable” in school environments, is influenced by the vastly different kinds and rates of parental feedback they receive at home (p. 51-2). Rather than automatically punish these students and further restrict them, we should seek to understand their background and work to “connect their interests and talents to the wide range of possibilities offered by our society and economy” (Barton p. 70).

Highlights of Group Discussion: In the educational system, we are often taught that there is a “right” and a “wrong”. Responses to questions can be either correct or incorrect, and behaviors can be either acceptable or unacceptable. However, in this chapter, we have discovered that this kind of attitude towards the classroom experience can be off-putting to some students, and actually cause them to become disinterested in learning. In order to provide a productive experience for all students, we should embrace questions and challenges to what counts as “socially acceptable,” while still emphasizing to our students the importance of understanding the dominant social code.

Questions to Pose:

- Should we/how can we, as educators, intervene in inter-student interactions to make sure no single student is dominating the scene and making others feel left out of an educational activity?

- How can we include different cultures or particular interests of students into the classroom?

- How can we encourage students to challenge authority and their identity without it being disrespectful to educators or the students feel that they are being “bad”?

Mission Statement:

There was no change in our mission statement aside from the qualifications made from last week’s readings.

Next Week’s Reading:

Chapter 6: Transformations – Science as a Tool for Change. Under the same assumptions as last week in that later chapters refer back to stories in previous chapters and hence a chronological approach towards our readings were adopted. Through this reading, we will be reading more personal stories of individual students with a focus on geographical locations.

Week 4- Mixing social justice and science: gender fluidity and sex

A majority of our discussions surrounded the idea of how to incorporate social justice in the science classroom and this video discusses one way to do that. The woman in the video talks about ways to incorporate sex and gender in a biology classroom by discussing the scientific implications behind sex and the idea that science is continuing to be discovered. For example there is more research that needs to be conducted to figure out more about the differences between sexuality and how much science has to do with that difference.

How can you be an ally and a scientist at the same time?

9/28/2015 PLC Challenge

In Urban Science Education for the Hip-Hop Generation, the presenter Dr. Chris Edmin explains how he uses hip-hop and rap in the classroom to connect with and engage his students. This ties into our PLC reading in that it highlights the importance/effectiveness of making content material culturally relevant to students. In addition, it gives students an avenue to narrow the authority gap by letting them connect class material to something they are already familiar with.

Questions to Pose:

- Would relating to students in this way reach every single student? What about the students who do not enjoy hip-hop music.

- Is it being stereotypical to assume that every urban child enjoys hip-hop music?

Mission Statement:

There was no change in our mission statement aside from the qualifications made from last week’s readings.

Next Week’s Reading:

Chapter 4: Power of Co-opting Science Spaces. Under the same assumptions as last week in that later chapters refer back to stories in previous chapters and hence a chronological approach towards our readings were adopted. Through this reading, we will be reading more personal stories of individual students with a focus on geographical locations. Since we weren’t to fully explore this chapter this week, we’ll revisit it in our discussion next week.

Scientific Literacy for All – Group 19

Facilitator: Pam Dominick

Notetaker: Cailey Solomon

This week we decided to read Chapter 2 of Teaching Science for Social Justice because we realized that each chapter is not a single vignette, but rather the chapters come together cumulatively to tell a story. When we read chapter 7 the previous week, we noticed that the narrator kept referring to situations that were mentioned in previous chapters. To get a complete view of what this book is trying to explain, we decided to skim Chapter 1 and read Chapter 2 thoroughly.

In Chapter 2, Kobe returned to school in hopes of gaining some knowledge on Science to ensure some backup career if his pursuit of sports did not work out as planned. He previously dropped out because he believed school was not a necessity in his life. After working with the after-school science project, he thought he would give the classroom another chance. Unfortunately, Kobe was welcomed with snide remarks from his teacher, mentioning, “he didn’t remember him, laughed, and informed him that it was too late for him to try to pass the semester” (23). This part of the story stood out for our entire group. As future educators, we noticed that this is not how a student-teacher relationship should be. If anything, teachers should want to encourage students to not only do well in school, but to stay present and active in the school community as well. Science classes should especially not play out in this manner because the material can be difficult and somewhat intimidating to teach in general. The chapter mentions that there is a goal for all students to gain scientific literacy, and that students in the more urban settings are “quantitatively lagging behind their more affluent and suburban counterparts” (23). If this is so, why did that one particular teacher decide to isolate Kobe, knowing that Kobe would not dare come back after being made fun of? As educators, we should realize that the inequalities are more present in these types of situations, where there is minimal encouragement for students to achieve higher than what they normally could see themselves achieving. It is easier to focus on the flaws and lack of knowledge that the students might have in certain subject areas, also known as the Deficit Model, but this is not conducive for learning or teaching (27). Why discourage students for doing something wrong, when instead you could be supporting and correcting their ways instead? Science teachers should make Science accessible to all students, and to do that they must understand the needs and wants of their students and incorporate that into their lesson plans and teaching methods. The last thing educators want to do is to scare a child away from a subject that is not only interesting, but also incredibly necessary to gain scientific literacy (and to also graduate).

Recent Comments